English

▾

English

▾

Ever wondered how simple jars of bubbling curds, grains or leaves preserved food long before refrigerators existed and what ancient kitchens might still be teaching us about food safety?

Fermentation, a process that long preceded modern refrigeration, is actually a remarkable biological method: microorganisms such as bacteria and yeast convert natural sugars and starches in food into acids, alcohols or gases, under anaerobic conditions. Over millennia, humans harnessed this metabolic magic to preserve perishable foods, enabling storage, longevity, and safety when fresh food was unavailable. From dairy in pastoral societies to grains, legumes, vegetables, and tubers in hunter-gatherer and agrarian communities, fermentation has become a global technique to increase shelf life, improve digestibility, lower toxins, and even add vitamins and nutrients to food.

In this post, we trace that transformation: from spontaneous, traditional ferments to carefully crafted microbial systems studied by scientists, and explore how ancient kitchens laid the foundation for modern food-safety and nutrition science.

The Roots: Fermentation, Humanity’s First Food Technology

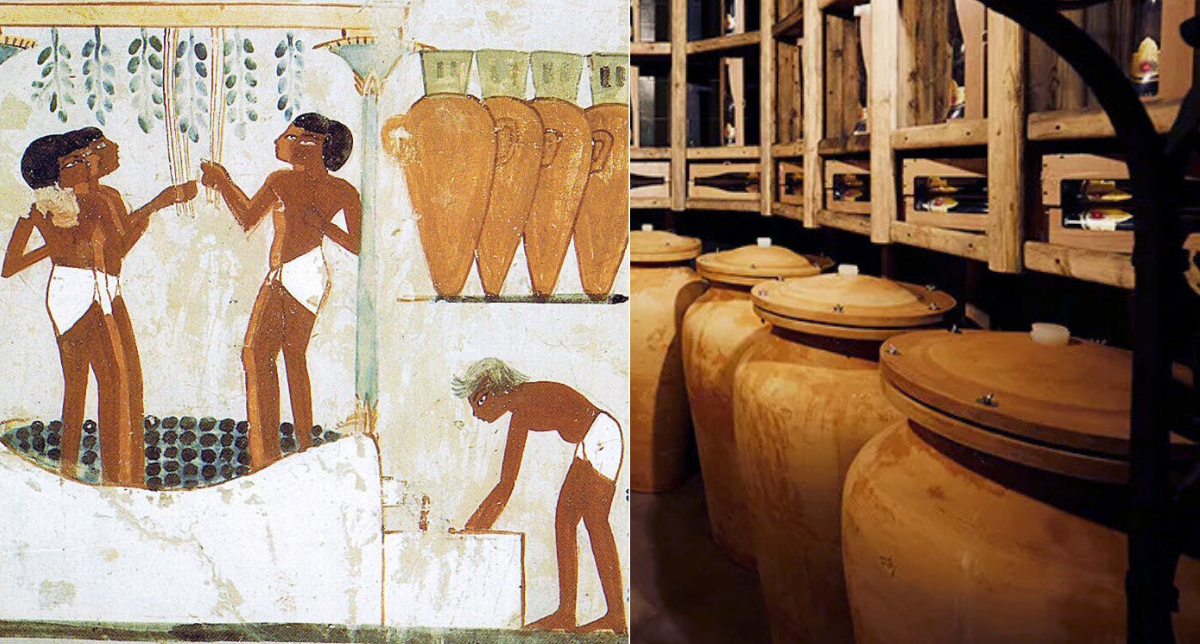

- The art of fermentation predates recorded history. Archaeological evidence and food-history research suggest that the earliest fermentations emerged spontaneously. For example when leftover milk curdled, or when cereal porridges soured during storage.

- As early agriculture and animal domestication took root ~10,000 years ago, fermentation became widespread: people realised that fermentation could preserve surplus harvests or milk, a simple, low-tech way to store food before spoilage set in.

- Over generations, these practices became cultural, refined regionally: each community developed its own microbial traditions, flavors, processes, laying the foundation for what we now call “indigenous fermentation.”

What Fermentation Does: Microbes, Preservation & Flavor

At its core, fermentation is microbial metabolism: bacteria, yeasts, sometimes molds act on sugars, proteins, or starches in food – producing acids, alcohols, enzymes, and other metabolites. Those chemical changes:

- Lower the pH (increase acidity) or produce alcohol / other antimicrobial compounds → making the environment hostile to spoilage or pathogenic microbes.

- Break down complex molecules (carbohydrates, proteins) into simpler, more digestible forms, therefore improving digestibility, reducing antinutrients, and making nutrients more accessible.

- Create distinctive flavors, textures, aromas — the “tang,” “umami,” “fizz,” or “earthy” notes we associate with fermented foods; making them culturally meaningful and delicious.

Traditional Fermented Foods Across Cultures

Human cultures everywhere harnessed fermentation, often shaped by the local environment, available resources, and culinary needs. Some examples:

- Dairy ferments: Milk from cows, goats, mares or other animals turned into fermented yogurts, drinks, cheeses, curds, or local dairy staples. These provided long-lasting nourishment and digestible proteins where fresh milk was perishable.

- Legume and grain ferments: In soy-growing regions (East, Southeast Asia, Himalayan belt), soybeans became fermented foods; cereals or grains elsewhere formed fermented porridges, breads, drinks.

- Vegetable- or tuber-based ferments: In colder climates or regions with seasonal produce, fermenting vegetables preserved vitamins and brought flavor when fresh produce wasn’t available.

- Beverages, condiments, and hybrid products: From fermented wheat or rice-based drinks to sauces, pickles, mixed ferments, the diversity shows adaptation to climate, food availability, social customs.

Ingredients and microbes shape global fermented food diversity

Why So Much Diversity?

Local resources & environment: Different regions had different base ingredients like milk (cow, goat, mare), soybeans, grains, cabbages, root vegetables, fish, tea, and their availability shaped what got fermented.

Traditional knowledge and microbial ecology: Because fermentation often used “wild” microbes or naturally present microbial communities, each region developed its own microbial heritage, contributing to unique flavors, textures, aromas, and nutritional properties.

Preservation and survival needs: Before refrigeration or modern canning, fermentation let communities preserve seasonal produce, store food for lean times, and ensure year-round nutrition.

Cultural identity & culinary traditions: Over time these fermented foods became woven into cultural rituals, daily meals, diets, festivals, carrying identity, heritage, taste, and social memory.

How Traditional Fermentation Became a Scientific Breakthrough

For centuries, fermentation remained “folk science”, an empirical, local, oral tradition. But modern scientific understanding of fermentation began to crystallize with the rise of microbiology (after pioneers like Louis Pasteur and others).

With biochemical and microbial research, scientists realized:

- Fermentation is carried out by live microbial food cultures. Bacteria (especially lactic-acid bacteria), yeasts, sometimes molds or other organisms — more than 260 species are used globally.

- In addition to preserving food, the microbial communities in fermented foods can also reduce antinutrients, produce vitamins, bioactive peptides, and antioxidants, and occasionally add "functional" or "probiotic" qualities.

- Modern studies link fermented-food consumption (with live microbes) to potential health benefits like improved gut health, better digestion, enhanced nutrient absorption, and possibly improved immune or metabolic health.

Food Safety & Nutrition: Fermentation as Early Food-Safety System

- The acids, alcohols, and other metabolites produced during fermentation inhibit spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms that reduce chances of foodborne disease.

- Fermented foods often remain edible and nutritious over long periods. This made them critical for food security, especially in climates or seasons where fresh produce or milk would spoil quickly.

- Nutritionally, fermentation can enhance digestibility, break down antinutrients, increase bioavailability of minerals, and produce vitamins or beneficial fatty acids that make foods more nutritious than their raw counterparts.

Modern Revival & Scientific Interest: Why Fermented Foods Matter Today

Despite the global rise of refrigeration, industrial food processing, and global supply chains — fermented foods remain relevant; in some respects, more than ever.

- Contemporary research (including a 2025 review) shows fermented-food consumption is associated with potential protective effects for metabolic health, cardiovascular health, maybe even neuropsychological outcomes.

- Fermentation offers a low-energy, climate-adaptive method of preservation. For rural or under-resourced regions, or places with erratic electricity or supply chains, traditional fermentation can help reduce waste, preserve harvests, and contribute to food security.

- There is renewed interest globally in artisanal, indigenous, “heritage” foods both for their unique flavors and for their connection to cultural identity. Fermented foods embody that heritage.

- Advances in food science and “omics” (genomics, metabolomics) are helping us better understand and preserve the microbial diversity of traditional ferments, possibly scaling them safely without losing their unique microbial character.

Challenges & Risks in Meeting Modern Food Safety Standards

Fermentation is powerful but it isn’t foolproof. As we scale and commercialize, or try to industrialize traditional ferments, several challenges emerge:

- Safety risks and microbial hazards: While many ferment-associated microbes are benign (or beneficial), some fermented products, especially low-acid or improperly handled ones, can harbor pathogens or toxins (e.g. harmful bacteria, formation of biogenic amines).

- Loss of microbial diversity / traditional strains: Scaling up often means standardizing with commercial starter cultures which may not replicate the full microbial ecosystem found in traditional, local ferments. That can reduce flavor complexity, nutritional or probiotic value, and cultural uniqueness.

- Consistency & reproducibility issues: Fermentation depends on numerous variables like temperature, humidity, raw-material quality, microbial load, and time. Slight changes can result in very different outcomes (taste, safety, texture). This variability is a challenge for modern food production aiming for uniformity.

- Regulatory, hygiene, and public-health demands: For fermented foods to scale or be commercialized across regions, there’s a need for safety standards, quality controls, and microbial testing, which traditional cottage-level methods often lack.

- Balancing tradition and modernization: There’s a tension between preserving traditional methods (and their microbial heritage) and applying modern food-safety norms and industrial consistency. Navigating that balance is tricky.

Why It Matters: Culture, Science & Future of Food

Food-preparation is only one aspect of fermentation. It serves as a link between microbial ecology and human culture, as well as between traditional knowledge and contemporary research. Communities all throughout the world have used fermentation to transform basic, perishable food into long-lasting staples that are nutritional, safe, and profoundly cultural.

Today, as we face climate challenges, food insecurity, loss of biodiversity, and health issues tied to diet, revisiting traditional fermentation could be purposeful rather than merely nostalgic. By combining ancestral knowledge with scientific tools, we can reclaim a sustainable, nutritious, and culturally rich food heritage.

French

French

Spanish

Spanish

Portuguese

Portuguese