English

▾

English

▾

October 2025 served as an alarming indicator of the persistent, complex challenges that the world's food supply chain faces. Although consumers frequently take the safety of the food on their plates for granted, a number of widely reported recalls and regulatory actions in North America, Europe, and Australia highlighted the urgent need for technological innovation, transparency, and vigilance. This month’s events were not rare incidents; rather, they were signs of more serious systemic flaws that the industry needs to confront.

A Month of Global Food Safety Incidents

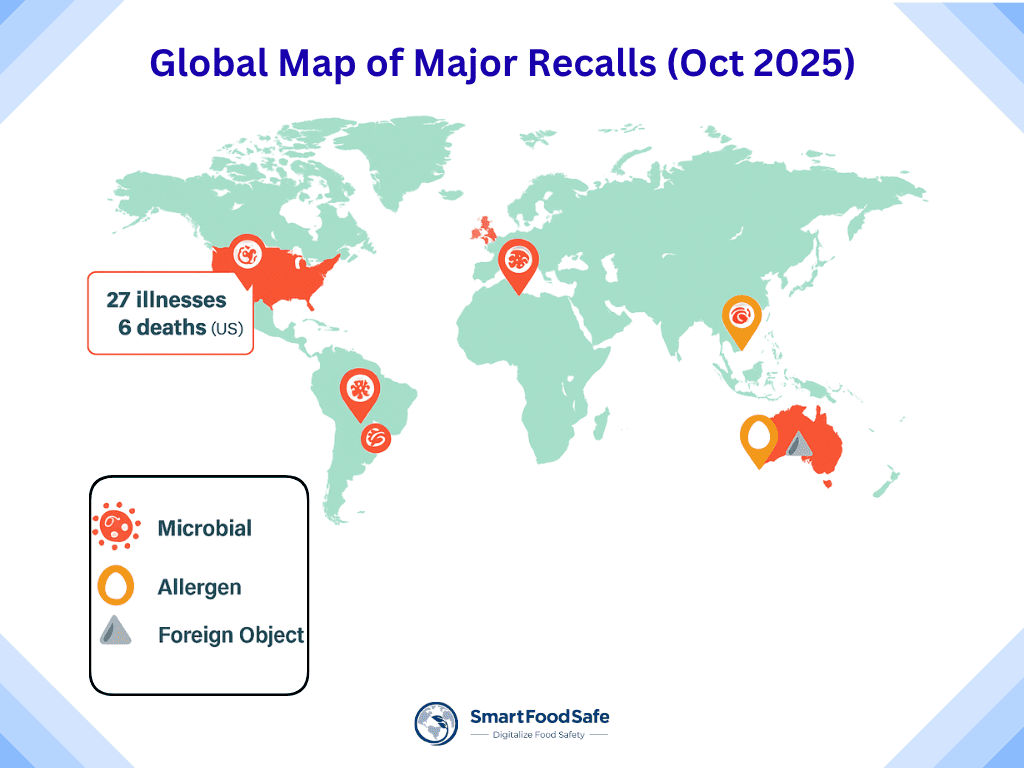

The news cycle in October 2025 was dominated by significant food safety events, highlighting a range of contamination issues from microbial pathogens to foreign objects.

In the United States, the month closed with a serious multi-state Listeria monocytogenes outbreak linked to refrigerated ready-made pasta meals sold at major retailers like Walmart and Kroger. This outbreak tragically resulted in 6 deaths among 27 confirmed illnesses, tracing the contamination back to a single supplier. Simultaneously, the FDA announced recalls for products ranging from kratom powder (Salmonella risk) to pre-cut peaches (Listeria risk) and fresh raw cheeses (Shiga-toxin E. coli), demonstrating the diverse pathways for microbial contamination.

The challenge was not confined to the U.S. North America also saw the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) warn of Salmonella in roasted pistachios. More notably, a massive voluntary recall of over 2.2 million pounds of Korean BBQ pork jerky by LSI Inc. was initiated after customers discovered wire fragments in the product. This foreign object contamination incident quickly became a cross-border issue, with Australia's food safety authority also recalling the same product, illustrating the interconnectedness of modern supply chains.

Meanwhile, Europe grappled with the long-term fallout of a prolonged Salmonella Strathcona outbreak, which had affected 17 EU/EEA countries since January 2023. The source was definitively traced to small tomatoes from Sicily, Italy, with the pathogen even found in the farm's irrigation water. This incident, which also affected the UK, Canada, and the U.S., highlighted the enduring risk posed by fresh produce and agricultural practices.

Beyond the immediate recalls, October brought significant regulatory movement:

- China unveiled a draft "Management Measures for Food Recall" to modernize its system.

- The U.S. FDA issued its first-ever import certification mandates under FSMA, requiring certain Indonesian shrimp and spices to be certified free of radioactive cesium-137 following earlier detections.

- The Codex Alimentarius Commission adopted new global standards, including updated purity criteria for vegetable oils and strengthened allergen-labeling requirements.

- The UK Food Standards Agency introduced updated Food Law Codes of Practice, moving toward a more flexible, risk-based approach to enforcement.

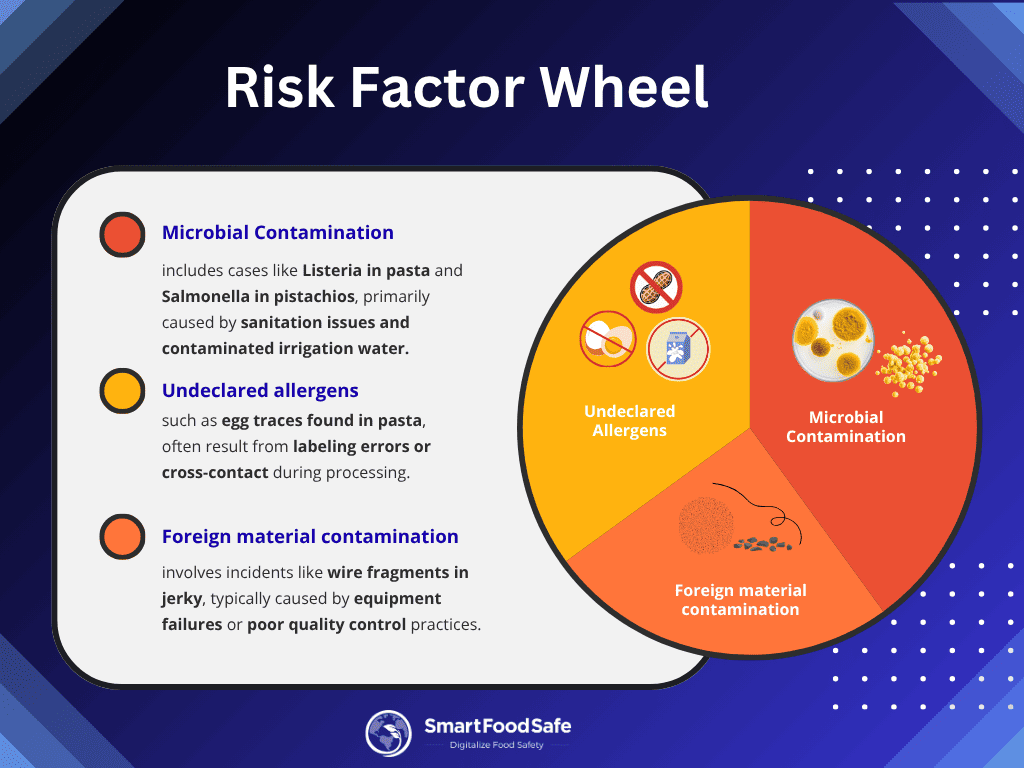

The Root Causes: Analyzing Common Recall Risk Factors

The events of October 2025, and food recalls in general, can be distilled into three primary categories of risk, each demanding a targeted preventative strategy.

| Risk Category | Description & October 2025 Example | Common Root Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Contamination | Pathogens like Listeria, Salmonella, and E. coli (e.g., Listeria in ready-made pasta, Salmonella in pistachios/kratom, E. coli in cheese) | Inadequate sanitation (processing/equipment), insufficient cooking/pasteurization, cross-contamination (raw/cooked), poor hygiene practices, contaminated raw ingredients (e.g., irrigation water) |

| Undeclared Allergens | The presence of a major food allergen not listed on the product label (e.g., Egg allergen in an Australian pasta meal recall) | Labeling errors, ingredient misstatements, poor change management, cross-contact during production (e.g., shared equipment not properly cleaned) |

| Foreign Material | Physical contaminants that pose a choking or injury hazard (e.g., Wire fragments in pork jerky, glass shards in pickled jalapeños) | Equipment failure (e.g., metal fatigue), poor quality control checks (e.g., lack of sieves/magnets/X-ray), human error, or packaging defects |

The common thread running through these incidents is the vulnerability of the supply chain. A single component failure, such as a farm's irrigation system, a supplier of a single ingredient, or a piece of processing equipment, can have catastrophic global repercussions as food production grows more complex and globalized. Due to the vast volume and rapidity of contemporary food distribution, millions of consumers may already be in possession of the tainted product by the time an issue is discovered.

The Path Forward: Technology and the Future of Food Safety

The food industry is quickly adopting a new generation of technologies to reduce these risks, which have the potential to change the food safety paradigm from one that is reactionary (responding to outbreaks) to one that is preventive. The scientific and technological developments reported in October 2025 offer a glimpse into this future.

1. Advancements in Smart Detection and Decontamination

The future of food safety hinges on the ability to detect and neutralize threats faster and more precisely than ever before.

- Rapid and Portable Sensors: Innovations are dramatically reducing testing time. Michigan State University researchers reported a new nanoparticle-based detection system (Glycan-coated magnetic nanoparticles) that can identify viruses and bacteria in a sample in just a few hours, a process that traditionally took days. This is complemented by the development of portable multianalyte sensors, for instance, the READ FWDx sensor (UT Dallas/EnliSense) that combines 16 impedance sensors on one chip to simultaneously test a food sample for multiple pathogens, pesticides, or antibiotic residues in minutes, enabling on-site microbial screening with minimal equipment.

- Advanced Imaging Platforms: Enhanced detection hardware is emerging, including systems that merge high-resolution microscopy with Raman spectroscopy, allowing users to locate and chemically identify microscopic foreign particles like plastic fragments in food samples with greater sensitivity and speed than traditional lab tests.

- Novel Decontamination Methods: Research is moving beyond traditional heat and chemical treatments. A study on edible "microneedle" patches loaded with bacteriophages (viruses that target bacteria) demonstrated the potential to eradicate nearly 99.9% of E. coli or Salmonella deep within meat samples, offering a targeted, chemical-free solution that could complement existing hygiene measures.

2. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Traceability

The complexity of the global food supply chain necessitates the use of powerful digital tools to manage risk and ensure transparency.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Risk Modeling: AI is proving indispensable for analyzing the vast amounts of data generated across the supply chain. A new FAO-Wageningen report synthesized 141 global studies, highlighting AI applications in automated pathogen detection, supply-chain risk modeling, and even social media monitoring for early outbreak detection. These tools promise faster hazard identification and can significantly augment regulatory oversight by predicting where and when a failure is likely to occur.

- Digital Traceability: The industry is heavily investing in Blockchain and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. By creating an immutable, digital ledger of a product's journey from "farm-to-fork," these tools enable near-instantaneous tracing of a contaminated item back to its source. This dramatically reduces the scope and duration of recalls, saving lives and minimizing economic damage.

3. Addressing Emerging Contaminants and Regulatory Adaptation

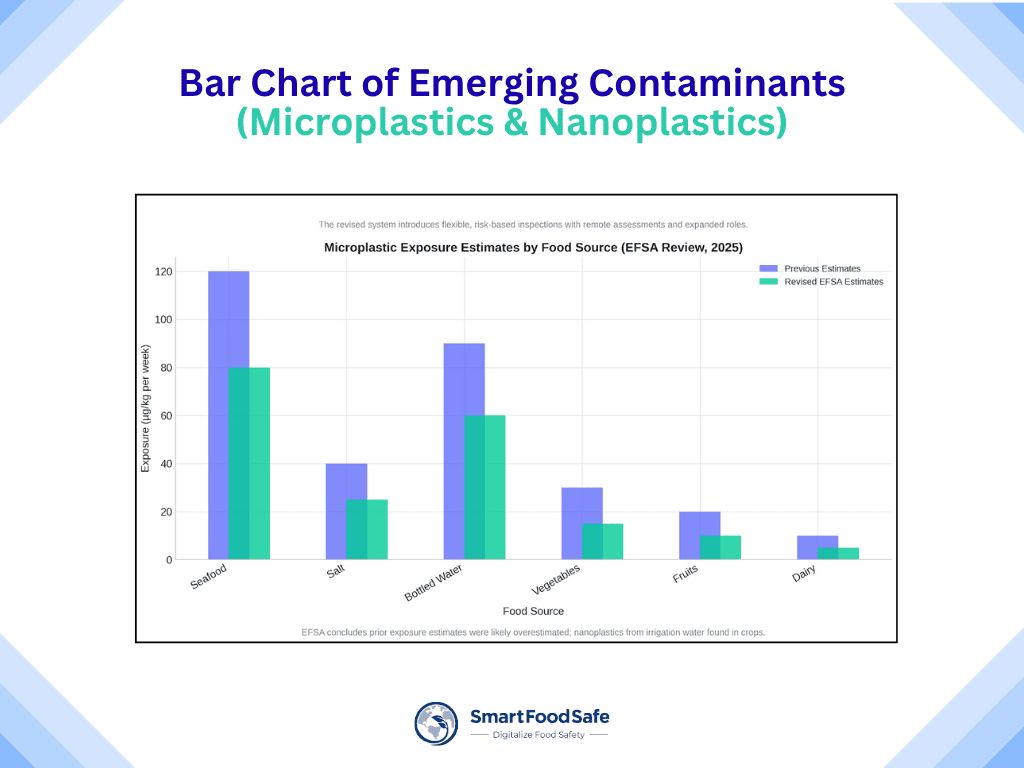

Beyond traditional threats, new challenges require both scientific and regulatory responses.

- Microplastics in Food: Research is intensifying on contaminants like microplastics. While one EFSA review suggested that human exposure from food packaging might be overestimated, other findings showed that nanoplastics in irrigation water can be taken up into edible plant tissues (such as radish roots). These studies underscore the need for better methods to quantify plastic contamination and assess health impacts, a call echoed by a 2025 review from UK researchers stressing the need for advanced sensors and global data sharing to detect new contaminants.

- Innovative Packaging: Though still in the research phase, "active" packaging technologies continue to develop. This includes edible coatings with antimicrobial agents or indicators that change color upon spoilage, which could provide an additional layer of safety and freshness monitoring directly to the consumer.

- Regulatory Modernization: Technological advancements must be matched by regulatory agility. The October 2025 regulatory updates, which range from the FDA's new import requirements to the UK's adaptable, risk-based enforcement codes, demonstrate a global trend toward better resource targeting through the use of data and risk assessment. International bodies like the Codex Alimentarius Commission continue to harmonize global standards, ensuring that safety benchmarks keep pace with scientific understanding and technological capability.

Why October 2025 matters

The October 2025 food safety incidents are a potent force for transformation. They show the industry's dedication to a safer future while also highlighting the persistent risks of physical and microbiological contamination. The food supply chain is entering a new era of unprecedented transparency and early control by utilizing AI, fast sensor technology, and digital traceability. The objective is unambiguous: to guarantee that the upcoming technological revolution not only boosts productivity but also essentially protects the well-being and confidence of consumers worldwide.

Essential Food Safety Glossary from October’s food-safety events

Below are concise term + one-line explanations you can drop into your blog to help readers quickly understand key concepts.

| Category | Term | Definition (One-Line Explanation) |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial & Biological Terms | Bacteriophage | A virus that infects and kills specific bacteria; increasingly used as a natural alternative to chemical disinfectants in food processing. |

| Listeria monocytogenes | A cold-tolerant bacterium that causes listeriosis, a serious infection dangerous to pregnant women, newborns, and the elderly. | |

| Salmonella Strathcona ST2559 | A specific Salmonella strain responsible for a multi-country outbreak linked to contaminated tomatoes in 2025. | |

| Shiga toxin | The harmful toxin produced by certain E. coli strains, responsible for the severe symptoms of STEC infections. | |

| Technology & Innovation | Active Packaging | Smart packaging materials that extend shelf life or indicate spoilage through antimicrobial coatings or color-change sensors. |

| Edible Microneedle Patch | A novel decontamination method using microscopic edible needles loaded with bacteriophages to kill pathogens inside meat surfaces. | |

| Nanoparticle-Based Detection System | A rapid testing method using engineered nanoparticles to detect pathogens or toxins in food samples within hours. | |

| Glycan-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles | Magnetic particles coated with sugar molecules to “capture” microbes for fast, precise lab identification. | |

| Smart Sensor / Multianalyte Chip | Compact electronic device that simultaneously tests for multiple contaminants such as microbes, pesticides, and heavy metals. | |

| Raman Spectroscopy (in Food Testing) | A high-resolution optical technique that identifies chemical contaminants based on their molecular vibrations. | |

| Supply-Chain & Regulatory Concepts | Blockchain (in Food Traceability) | A secure digital ledger that records every step in a food’s journey — from farm to store — enabling transparent recall tracking. |

| Digital Traceability | The use of connected digital tools (e.g., IoT sensors, barcodes, blockchain) to instantly trace contaminated products to their source. | |

| Traceability Ledger | A digital record of each stage in a food’s production and distribution, allowing faster, targeted recalls. | |

| Import Certification Mandate | A requirement that imported food must have official safety documentation before entering the market. | |

| Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) | A U.S. law emphasizing prevention of foodborne risks rather than reaction, strengthening FDA oversight. | |

| Food Law Codes of Practice (UK) | Guidance from the UK Food Standards Agency outlining how local authorities enforce food-safety laws. | |

| Codex Alimentarius Commission | The joint FAO/WHO body that develops harmonized international food-safety and quality standards. | |

| Contamination & Risk Types | Microplastics / Nanoplastics | Minute plastic fragments (often invisible) that can enter food via packaging or the environment; health effects remain under study. |

| Foreign-Object Contamination | Physical contaminants such as glass, metal, or plastic fragments accidentally present in food. | |

| Allergen Cross-Contact | When a food allergen unintentionally transfers to a non-allergen product, causing potential allergic reactions. | |

| Undeclared Allergen | A major allergen (nuts, eggs, milk, etc.) present in a food but not listed on the label, leading to recalls. | |

| Irrigation Water Contamination | Pathogens or pollutants in farm-water sources that can infect crops, often implicated in produce-related outbreaks. | |

| Scientific & Specialized References | Cesium-137 (Cs-137) | A radioactive isotope monitored in imports after nuclear incidents; the FDA recently required certification for shrimp and spices to prove absence. |

| Hazard-Based Risk Model | A predictive AI or statistical system that estimates where a food-safety failure is most likely to occur. | |

| FAO-Wageningen Report (2025) | A landmark UN-backed study highlighting artificial-intelligence applications in global food-safety monitoring. |

French

French

Spanish

Spanish

Portuguese

Portuguese